It was once a trope of rock n roll that ageing pop stars should have called it a day long before they started to go grey, lose their voice and run out of ideas. Pop music, after all, pretty much invented the generation gap in the latter half of the 20th century. From outrage at

Elvis’s wiggling hips, to shock at the Beatles’ long hair, Bowie’s androgyny or

Madonna’s wardrobe, the ‘olds’ just didn’t get our music. (My mum dismissed

much of it as ‘just a noise’.) And the last thing we wanted to see was our rock

stars starting to resemble our mums and dads. There’s many a brickbat come the

way of old rockers either churning out old hits or trying to remain relevant

with a new album that just evidenced their waning powers.

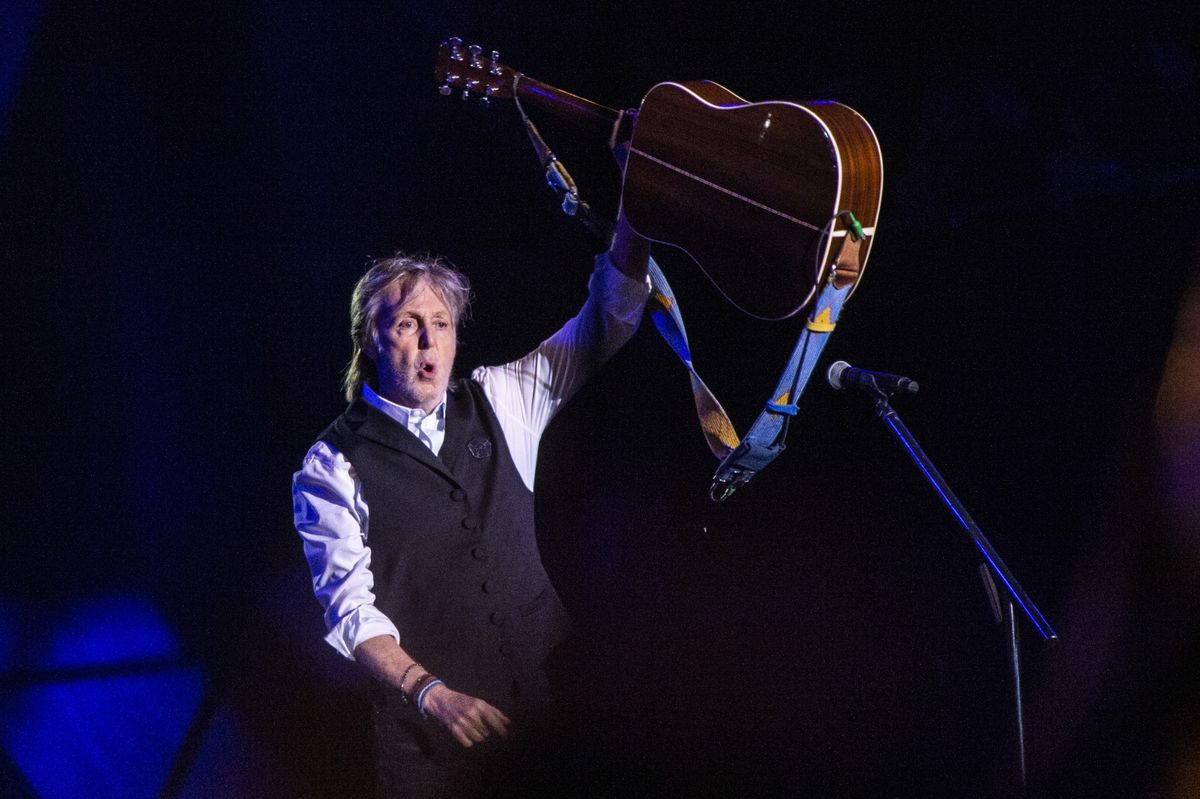

This has changed in the 21st century. The idea of Paul McCartney headlining Glastonbury at 80 would once have been laughed out of existence – this was a man, after all, who had foreseen a life of pipe and slippers when he was 64. Joining him on stage were 72-year old Bruce Springsteen and young pup Dave Grohl, 53. Supporting was Noel Gallagher, another man in his 50s whose pomp was nearly 30 years ago. And the crowd – a mix of ages, and in fairness not as young as those cheering on Billie Eilish the night before – lapped it all up with absolute glee. Gallagher remarked afterwards that for kids to still be singing along to Oasis songs two generations down the line is amazing to him. And McCartney, even with his voice failing, was getting rave reviews for an epic set that will go down as one of the great Glastonbury performances.

There is a school of thought which suggests that rock n roll itself got old, so the popularity of old acts churning out familiar tunes should not surprise us. Rock music has been surpassed as the primary form of pop by Hip Hop and R&B. The average 18 year old can’t bunk in to

Glastonbury as our generation did, because it’s now a massive corporate event

and the gaps in the fences have long since been plugged – so the organisers aim

for an older, more affluent audience.

These points have some merit, of course -indeed, the decline of rock n roll sometimes threatens to create a new generation gap with middle aged moaners making ‘hilarious’ jokes about putting a ‘c’ in front of rap or just not ‘getting’ the music their kids like. But the

reality is that new music always came along and some of us always actively sought it out – and still do. And meanwhile, a lot of younger listeners appear to love music as ancient as The Beatles, several generations of teens since Beatlemania. My 15 year old has eclectic taste: Taylor Swift and Olivia Rodrigo are joined by Artic Monkeys, Oasis, Bowie and yes, The Beatles, on her playlists.

Perhaps new found credibility of ageing rock stars owes most to the fact that so many of them have turned out critically acclaimed albums in the 21st century. David Bowie said many years before his spectacular renaissance that at some point, an older act was going to produce a brilliant album and he hoped it would be him. Well, it wasn’t just him: McCartney, Bowie, Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Tom Waits and Leonard Cohen have all produced material

in the last decade or so to compete with their best years. Gallagher joked on the Glastonbury stage that he knew people weren’t there to hear his High Flying Birds output, but it’s actually massively underrated. Rock music may not be as dominant, but it’s part of the cultural furniture: old stagers who are experts in their craft and are still open to new ideas suddenly feel relevant again.

The ageing rocker stereotype arguably gained real strength from the sad images of an ageing Elvis stumbling and muttering through live sets in the 70s; perhaps the many young deaths of pop stars still seemingly at the peak of their powers helped in a way too. Pop careers were once automatically considered brief. The Sex Pistols had only one proper album, Amy Winehouse only two: the idea of the young star who burns brightly and briefly before crashing has always had its tragic appeal. There is also certainly an appetite among middle aged fans to see iconic acts because ‘it may be the last time’ – and the word is that the Rolling Stones and Elton John have been putting on shows to remember on their current tours. Virtually every 80s band I grew up with seems to be touring these days too. Nostalgia is certainly a part of the attraction.

Some will argue that young people don’t listen to music anymore, or at least not in the same way. Technology plays a part. The advent of streaming and songs being popularised through Tik Toks, Netflix dramas and ads – has accelerated a trend where some younger audiences were more likely to love individual tunes than artists. The popularity of You Tubers, Tik Tokkers and gamers as ‘influencers’ takes some of that space away from musicians. And modern music production can hide a failing voice or fading musicianship (witness Liam Gallagher singing live now as opposed to on record). But tech and changing tends are not the whole story: people will always love music. If anything there is less of a generation gap on music now that at any time since rock n roll emerged in the 1950s.

That, I think, is the real change. Pop music is no longer just a thing for young people. There isn’t an older generation dismissing it as ‘noise’, its shock value long since disappeared and now it just ‘is’ – in its many different genres. The icons are no longer derided but celebrated, a man my age can enjoy nostalgia for great tunes of the past while continuing to seek out and enjoy new music. I think we’re all better for it.